Discursus de bello Moscovitico

On February 24, 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. It was considered an unlikely event given several factors, including the insufficient Russian troops amassed at the Ukrainian border.

To date, the Russians have suffered many defeats, notably failing to capture Kyiv, make Ukraine surrender, or even take Kharkiv - a city barely 40 kilometres from the Russian border. The Russian army performed significantly less well than estimated, and almost three months after the start of the Russian invasion, it is unlikely that they’ll manage to achieve their goals.

Numerous factors prevented Russia from achieving its war aims, including overestimating its military capabilities and underestimating Ukrainian military strength, logistical problems, a lack of soldiers, corruption, and an army command that hasn’t significantly evolved since the USSR, making units less agile in combat.

In fact, in early February, a Russian military expert, Colonel Mikhail Khodorionok, published an article calling for a “blitzkrieg” and explaining why attacking Ukraine would be a bad idea.

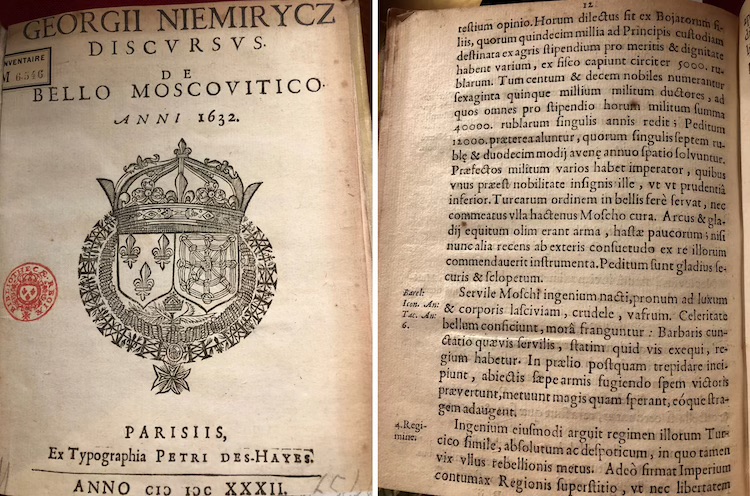

We should mention the work written in Paris in 1632 by Georgii (Yurii) Niemirycz, a Ruthenian (Ukrainian) nobleman. His work is called “Discursus de bello Moscovitico” and describes the war with Muscovy - the country we know as Russia today.

We will quote a few excerpts that draw a rather interesting parallel with the ongoing Russian-Ukrainian war. In addition, it’s worth noting that in the text, we won’t find the word “Russia” or “Russian” for a simple reason - the name of this country in the 17th century was Muscovy.

He begins by describing the tense geopolitical situation anticipating war, opening the text with the phrase “Strepebat iam longo tempore Moſchus […]”, which can be translated as “It’s been a long time since the Muscovites have been making noise”. His text appeared in the same year as the outbreak of the Smolensk War (1632-1634), pitting the Republic of Two Nations (the Polish-Lithuanian-Ukrainian state) against Muscovy.

Comparing the troops of his homeland and Muscovy, he notes that Muscovite troops follow Turkish order and that Muscovites don’t care about provisions: “Turcarum ordinem in bellis ferè ſervat, nec commeatus vlla hactenus Moſcho cura”. And one of the Russian army’s considerable shortcomings at this stage of the war is logistics and provision.

Niemirycz also describes the character of the Muscovites, writing the following: “Servile Moſchi ingenium nacti, pronum ad luxum & corporis laſciviam, crudele, vafrum. Celeritate bellum conficiunt, morâ franguntur." This can be translated as follows: “The Muscovites have acquired a servile temperament, inclined to luxury and libertinism, [are] cruel and devious. They finish the war with speed but become broken by delay.”

It is easy to notice that the Russians aimed for blitzkrieg but failed. The delay has broken their offensive capabilities and now threatens their military campaign.

Describing Muscovites (today’s Russians), he goes on to describe the regime of their country - Muscovy - as “absolute and despotic” and “similar to Turkish”, where “rebellion is hardly feared” ("Ingenium eiuſmodi arguit regimen illorum Turcico ſimile, abſolutum ac deſpoticum, in quo tamen vix vllus rebellionis metus").

As for the main power of Muscovite forces, Niemirycz points out that it “relies on men rather than soldiers, on numbers rather than strength” - ("Præcipua virium hoſtilium potentia hominum potiùs quàm militum, numero quam robori nititur"). This aspect is quite striking, as both the Imperial Russian Army and the Soviet Army relied on numbers and not quality. It also applies to the modern Russian army, and the current Russian-Ukrainian war confirms it.

He goes on to describe many things, including treaties, shares his ideas about defending his country, and insists that the Muscovites can only be defeated in Muscovy “like Hannibal in Africa” ("Moſchus nonniſi in Moſcovia ſuperari poteſt, vt Annibal in Africa").

His book can be found at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) and should be translated into English and French.